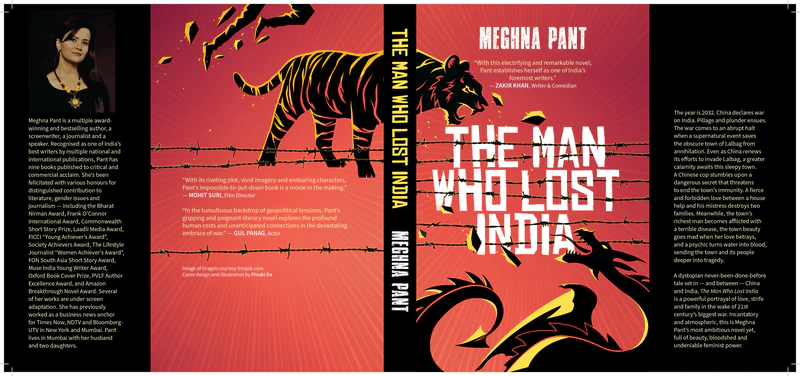

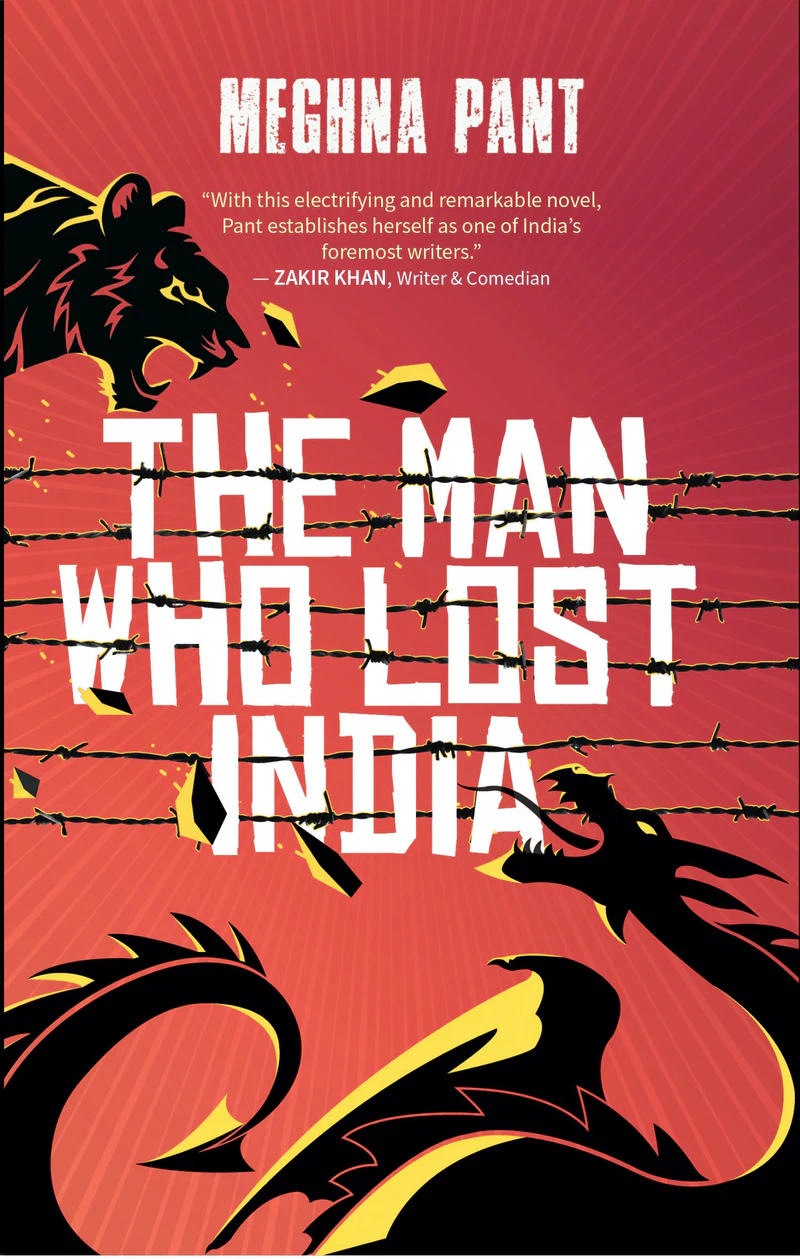

Author Meghna Pant’s launch of her latest novel The Man Who Lost India will be held at Crossword Bookstore (Kemps Corner) by Suchitra Pillai, Anu Menon, Neil Bhoopalam and Aniruddha Guha on February 23 from 6-8 PM. In a chat with culturecrossroads.ca, Meghna shared her inspiration behind the latest book and more.

Excerpts

What’s the inspiration behind The Man Who Lost India and what really pushed you to write a dystopian war novel? Considering it’s very unlike your other books.

The genesis of this book is for three reasons: MCP – misogyny, curiosity, and patriotism.

Misogyny: Twelve years ago, a fellow author––male, of course––said that women can’t write war novels. As a heretic, I wanted to debunk this stereotype. So here it is: The Man Who Lost India –ten years in the making and also the first time that an Indian woman has written a dystopian war novel! I didn’t know I was making history by writing the book, I was just trying to prove a chauvinist wrong! So, I hope I have done justice to my gender and more women write in genres that they’re told they can’t write in!

Curiosity: My Naniji, bless her departed soul, had once told me a story about the 1962 Indo-China war. She spoke about how women like her threw their jewellery at passing army trucks and how my Nanaji brought government gold bonds to aid India in the war. This sparked my interest on the indelible scars that war leaves on families, individuals, lovers, artists, entrepreneurs, people like you and me––bringing us together, as much as tearing us apart. India and China share a 3,500 km border and have interacted with each other for over 2,000 years. China is India’s most formidable enemy and her most important neighbour. It is remarkable then that our people know so little of each other––what we think, how we live, our customs and philosophy. Or even the cuisine. I was curious about our neighbour. As a child of the 1990s living in a metropolis like Mumbai I have been fortunate not to be a victim of war. But I wanted to understand what an actual war––not annihilative like a nuclear war, neither archaic like stones and spears, would entail. I wanted to examine the toll that extends beyond the battlefield. I wanted to deconstruct the human cost of war using physical, emotional, social, economic, and cultural dimensions. These curiosities led me to write this book.

Patriotism: The truth is that an Indo-China war eight years down the line will not just be about Tibet, or Bhutan, or Myanmar, or Maoism, or Sikkim, or Dolkun Isa, or the South China Sea, or the Chinese insurgencies in India’s northeast, or CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor), or China’s presence in POK, or the border rivalry between India and China, or the One Belt One Road initiative, but a cumulative of the same. This animosity will only intensify as the world begins to fight over limited resources due to climate change. Therefore, a collision course on the roof of the world is inevitable. And terribly fascinating.

Like any war that reverberates across generations, perpetuating cycles of violence, trauma, displacement and economic destruction, a 21st century war between India and China will destroy both nations. It shows us how in war, like in death, we find ourselves alone. But in the 21st century shouldn’t we be talking of empowering instead of overpowering?

The Man Who Lost India is therefore my small effort to unpack India’s China challenge. To serve as a wake-up call to the international community to prevent such a catastrophic event. We have to raise awareness about the geopolitical tensions in the region and encourage dialogue, diplomacy and conflict resolution to prevent escalation. By providing not just a historical but future perspective in the wake of climate change we can grasp the deeper roots of contemporary issues, raise awareness and foster a deeper understanding of the issues at stake. By highlighting the human suffering and devastation that war brings, this book may contribute to prevent violence, promote dialogue and cooperation, and improve bilateral relationships between the two countries.

The Man Who Lost India is also my small contribution to promote peace and stability in a world that is going to be devastated by climate change. It is so my beloved country India not just survives but thrives despite the havoc this century will unleash.

This is perhaps the first time an Indian woman has dared to write a dystopian war novel. Why do you think women writers stay away doesn’t his subject?

Because they’ve allowed patriarchy to get inside their heads. But stories don’t have a vagina or a penis, so how can they have a gender?

Historically, war literature has been predominantly male-dominated, with a focus on combat, heroism, and masculinity. But women writers have written war novels and women directors have directed war movies, offering unique perspectives on conflict and its impacts. They have often challenged stereotypes associated with both war and the act of writing about war. Women writers entering this genre have also brought new perspectives, often consciously confronting and subverting stereotypes, contributing to a more diverse and inclusive portrayal of war literature, and the representation of women’s roles within them. They’ve offered alternative narratives that highlight the diverse experiences and perspectives of those affected by war. By centering women’s voices and experiences, they contribute to a more nuanced understanding of conflict and its human toll. Not the ephemeral or deciduous impact of war as captured by the male gaze, but the lasting impact by delving into the emotional and psychological impact of war on individuals and communities.

For example, Pat Barker’s Regeneration Trilogy challenges stereotypes by focusing on the psychological and emotional effects of war, particularly on soldiers’ mental health. Barker’s exploration of trauma, shell shock, and the complexities of human experience during wartime offers a counter-narrative to the glorification of battle.

Similarly, authors like Virginia Woolf, Rebecca West and Vera Brittain, among others, have also challenged stereotypes through their war writings. Their works often delve into the experiences of women during wartime, highlighting their roles beyond the battlefield as nurses, caregivers, and activists. By foregrounding these often overlooked perspectives, these writers disrupt stereotypes about women’s passive roles in war narratives.

These writers, among others, consciously challenge stereotypes by bringing their unique perspectives and storytelling styles to the genre, offering a more diverse and nuanced portrayal of war and its effects.

In essence, women writers who have tackled war novels have consciously confronted and subverted stereotypes, contributing to a more diverse and inclusive portrayal of war literature.

It took 10 years! What was the most difficult/gratifying part of the process?

I have to confess that I experienced cognitive dissonance––like some people if they see a celebrity they love––and didn’t actively pitch the book out. I was consumed by this canonical fear that the book took so much out of me, and it was still not perfect. I wanted the book to be perfect. So, it sat in my laptop for six years. That was the toughest part.

Till I realised you can’t ever reach perfection, but you can believe in an asymptote toward which you are ceaselessly striving. I gathered the wherewithal to pitch it out and send the book out. When I read it now, I can safely call it my magnum opus––the best I’ve written, and that for me is perfection. It is always about your value of the thing, not the thing itself. That is as gratifying as it gets.

Can you provide some insights into the themes of war and conflict addressed in your novel?

The year is 2032. China declares war on India. Pillage and plunder ensue. The war comes to an abrupt halt when a supernatural event saves the obscure town of Lalbag from annihilation. Even as China renews its efforts to invade Lalbag, a greater calamity awaits this sleepy town. A Chinese cop stumbles upon a dangerous secret that threatens to end the town’s immunity. A fierce and forbidden love between a servant and his mistress destroys two families. Meanwhile, the town’s richest man becomes afflicted with a terrible disease, the town beauty goes mad when her love betrays, and a psychic turns water into blood, sending the town and its people deeper into tragedy.

A dystopian never-been-done-before tale set in – and between – China and India, The Man Who Lost India is a powerful portrayal of love, strife, and family in the wake of 21st century’s biggest war. Incantatory and atmospheric, this is my most ambitious novel yet, full of beauty, bloodshed, and undeniable feminist power.

What do you hope readers will take away from The Man Who Lost India after attending the book launch and reading your novel?

The book is apolitical but also deeply political, without being didactic or jingoistic. It spotlights the politics of nations, gender, class, power, love, and individuals, and ultimately how politics can be used to broker peace instead of hate. I hope my readers find it educative, immersive, and enlightening. I hope they question why India and China will go to war, who will win in this scenario, what will save India from China’s hegemonic demonic wrath, and who will save India if all is lost. I hope they become more aware of the catastrophic effects of climate change.

Ultimately though, for an author, an ideal reader is someone who doesn’t ask you for a free copy, buys your book, reads your book, talks about it to others, and puts an Amazon review. So, I hope that’s my readers biggest takeaway. Buy good books and talk about them!

How did the collaboration with Suchitra Pillai, Anu Menon, Neil Bhoopalam, and Aniruddha Guha for the book launch come about, and what significance does their involvement hold for you?

It’s amazing to see celebrities whose work I’ve grown up watching and admiring come out in support of me, despite the Mumbai traffic, despite having better things to do, despite it not involving the glitter of mad fame. This altruism––the love for words, the respect for talent, the recognition of hard work, and the support of female authors who have largely been marginalised the world over––is significant not just for me but for women all over our country. May this tribe increase!